research supporting

the use of silicone in medical devices had been compiled before Cronin and

Gerow employed it in the mammary prosthesis.

1962 marked the first implanting of a mammary prototype. For the next two

years, selected surgeons used the implants in clinical trials to obtain

information on their performance, both long- and short-term, before Dow Corning

took the Cronin implant fully to market in 1964. Additional support for the

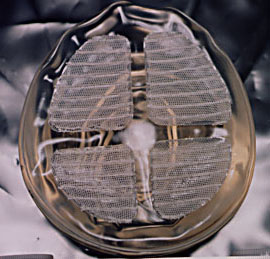

implants was found in the hydrocephalic shunt's performance results, since it

used the same elastomer. By 1962, four-thousand shunts had been placed in

children's brains, treating their hydrocephalus and saving their lives, all

without any apparent adverse effects [36].

Also, in 1962, the National Institute of Health funded the Battelle Memorial

Institute to conduct research[37] on the

stability of silicone implants in animals. The Institute's two-year study

focused on the effect of the body on the various polymers studied, which

included Polyethylene, Teflon, Mylar, Nylon, and Silasticreg.. In particular,

the study concentrated on the polymers' tensile strength and elongation, along

with the reaction of the implant site to the polymers. (Tensile strength is a

measure of the polymer's ability to withstand elongation forces.) The studies

used mongrel dogs as test sites, implanting samples of all five materials in

each. The plastics were recovered after six, eleven, and seventeen month

intervals. Their tensile strength was recorded before implantation and after

each removal, to track any loss, along with any elongation due to implantation.

After 17 months, Silasticreg. showed little decrease in tensile strength and

slight elongation. According to the study:

Changes [concerning tensile strength and elongation] in the Silasticreg.

and Mylar are not believed significant. . . In general, minimal local tissue

reaction was observed grossly at nacropsy. There was no gross evidence of

tumorigenesis either at the site of implant or in other organs and tissues.

No irritation or inflammation was seen . . . [However, the Silasticreg.

implant was observed to have] a poorly defined capsule which was

accidentally incised. As in previous necropsies, a great deal of difficulty

was encountered in locating the site of the flank implant. The Silasticreg.

strips were folded and wadded into a ball - no evidence of irritation or

local tissue reaction other than the connective tissue encapsulation. . .[38]

(Encapsulation is a common, but unharmful, foreign body reaction to any

implanted device, where tissue walls the device off from the rest of the body[39].) The

study also provided a histological

report on the 17-month findings. (Histology is the study of tissues[40].) The histological findings on

Silasticreg. showed "fibrous tissue segment without apparent inflammatory

reaction."

Simultaneous to the introduction of the Cronin implant to market in 1964, Dow

Corning contracted Food and Drug Research Laboratories, an independent research

company, to complete more long-term testing on the implants, which had already

been followed for two years in the clinical studies and seventeen months in the

Battelle study. In the three-year Food and Drug Research Laboratories

experiment, eleven polysiloxane compositions were implanted ". . . into

intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intraperitoneal sites in sufficient numbers to

permit samples and surrounding tissue to be removed at a number of periods

prior to sacrifice of the animals . . . The design of the study provided for

replication of each treatment in three dogs, restricting one type of

polysiloxane within each given dog, but permitting as many as four

replications of each product and site combination in a given animal."[41]. These silicones were implanted "over

protracted periods" in five forms: "solid film, perforated film, sponge,

amorphous forms, and miniature artificial breasts."[42] Microscopic examination of tissue

reaction was completed at three, nine, twenty-four, and thirty-six months. The

results of the study, published in 1968, proved encouraging for the use of

silicone in medical implants, especially in mammary prostheses .[43]

Although implants were first targeted at mastectomy patients, even Cronin and

Gerow would have been able to surmise the general population's desire to use

the mammary prostheses for enhancement as well. Thus, other manufacturers

developed similar implants, in response to a market which grew as women opted

for cosmetic breast procedures. However, Dow Corning, where the implant

originated, remained the industry leader. Dow Corning continued to look for

improvements to the implant, developing a new outer lining in 1968. This

elastomer envelope, while thinner, was also seamless. (At times, the line

where the two halves of the original implant were joined was noticeable under

the upper portion of the breast.) The seamless envelope was all one elastomer,

a thinner covering that provided even more aesthetically pleasing results.

Go on to Part 6

With over 10 years of research

already completed on it, silicone was a natural candidate for use in breast

reconstruction. In addition, it had already been utilized in other medical

applications, such as the hydrocephalic shunt and life-saving pace-maker

described earlier. These cases could provide information on the long-term

effects of silicone on the host.

With over 10 years of research

already completed on it, silicone was a natural candidate for use in breast

reconstruction. In addition, it had already been utilized in other medical

applications, such as the hydrocephalic shunt and life-saving pace-maker

described earlier. These cases could provide information on the long-term

effects of silicone on the host.