Massalia and surrounding tribes.

After Cunliffe 1988,

fig. 16

"Hellenization" is the process by which non-Greek peoples were made more or less Greek, acculturated if not assimilated into Greek culture. Hellenizein, mastery of the Greek language, comprised but one of several tools in this process, if perhaps the most important (Momigliano 1975, 7 ff.) -- a barbaros who speaks Greek is a contradiction in terms. Greek colonies were established throughout the Mediterranean from the early Geometric into the Classical era; the Hellenistic kingdoms formed after the conquests of Alexander the Great carried Greek culture even further into barbarian lands. Greeks abroad did not go native; instead, they brought what they could of Greekness with them and became, if anything, more emphatically and self-consciously Greek. They built cities, introducing urban structures and ideas into lands often innocent of them. Those cities contained civic centers, agoras, sports facilities, theaters, temples, fortifications, and Greek houses -- structures and institutions that helped perpetuate Greek culture abroad, and not incidentally, Hellenize the locals.

|

Massalia and surrounding tribes. |

The only major Greek colony in the "Celtic" lands was Massalia (Marseille) near the mouth of the Rhône, established ca. 600 BCE by Phocaeans from Asia Minor who had been threatened or displaced by the Persians. The territory around Massalia was inhabited by the historically shadowy Ligurians; the "Celtic" name of the local tribe (Segobrigii) is suggestive, and Massalia was certainly surrounded by "Celts" during the historical La Tène period. By the third or second century BCE, the local "Celts" used the Greek alphabet in Gallic inscriptions. Strabo describes Massalia in the first century BCE as a school for barbarians (IV.1.5), clearly a practical one in that the contracts with neighboring "Celts" were written in Greek (IV.1.5). Historians do not, however, recount the process by which this degree of Hellenization was achieved, nor how early it began. Massalia's self-representation in the Treasury at Delphi and in its own architecture emphasize its Greek and then Roman nature; relations with the locals were apparently both profitable and often hostile. The sources describe "a city which had decided to remain unchanged in its archaic Hellenic shape" (Momigliano 1975, 56). Little information about its non-Greek neighbors is forthcoming. We can assume that the presence of Massalia nearby piqued "Celtic" curiosity. Just as exposure to Italian luxuries must have played a part in enticing the "Celts" into invading Italy , no doubt Massaliote wealth sparked "Celtic" acquisitiveness, leading to fourth-century incursions. Pottery-making in the Massaliote manner and, significantly, the drinking and cultivation of wine became quite prevalent among the inhabitants of the Rhône basin (Dietler 1990). It is probable that local economies evolved in response to the Greek traders in their midst, capitalizing on their control of the inland waterways and roads, and finding a ready market for raw materials and slaves. None of this indicates any true mingling with Greeks before the Roman period; instead, the Hellenization we find in the immediate area surrounding Massalia appears to have been limited to facilitation of the amount of contact required for economic gain and little more.

Massalia is not the only, or even the principal, point of contact by which the "Celts" could be Hellenized. "Celts" served as mercenary soldiers throughout the Mediterranean, including stints both with and against Greeks. They were extremely mobile, invading Italy as far as Rome in the early fourth century; Greece to Delphi in the third; and settling in Hellenistic Anatolia. "Celtic" mercenaries in Ptolemaic Egypt wrote inscriptions in Greek (Momigliano 1975, 53) . Finally, a variety of Greek and Italian objects found its way into "Celtic" Europe by many different roads, probably involving contact with Greek traders at some point. The "Celts" had ample opportunity to observe the Greeks; they showed themselves receptive to Greek wine and to learning the Greek language when expedient. It remains to question how much active "Hellenization" can be said to have taken place in the late Hallstatt and early La Tène periods and what effect that may have had on "Celtic" art.

The conclusions reached in this study parallel, on an art-historical level, the results of recent anthropological discussions and the interpretation of archaeological contexts. Challenging the Hellenization model, I argue that imports from the Mediterranean and adaptation of Mediterranean elements do not in fact prove "Celtic" emulation of Greek culture; nor do they represent "Celtic" self-definition as "barbarian" vis-à-vis the Mediterranean higher cultures [I.]. Models postulating any kind of dependency on luxury goods imported from the south are without archaeological foundation.

This is not to say that world-systems or center-periphery models cannot explain the dynamics within "Celtic" localities; together with peer-polity interregional interaction theory, these anthropological reconstructions may provide our only path toward understanding developments within the "Celtic" lands, in the absence of written records. My contention is that the centers are to be sought within the "Celtic" area itself, and the dynamics must be comprehended first within the local system, then within interregional "Celtic" networks, and finally within the contiguous systems of Northern Italy and Eastern Europe [II.].

Study of "Celtic" art has been informed by the diffusionist bias underlying the Hellenization model [III.]. It has consisted to a great extent in the search for Greek elements and interpretation claiming emulation of Greek cultural elements together with visual styles and motifs. These studies fail to show how the specific images and their associated ideas would have been transported into the "Celtic" lands. There is discontinuity between the chronology of "Celtic" art and the history of interaction between "Celts" and the Mediterranean. The transmission of orientalizing elements via the Greeks rather than directly from the East or through Italy is not convincingly argued. The imported objects were used within the context of local practices, just as "Celtic" objects were used; unsurprisingly, the artistic importations were also entirely subsumed into the local visual system. Examination of the archaeological contexts of the the Mediterranean imports found in "Celtic" tombs reveals "Celtization" of the objects rather than "Hellenization" of the culture.

The seventh, sixth and fifth centuries B.C.E. saw the development and full flowering of the Greek city state; Greek Orientalizing, Archaic and Classical art; and the writing of Greek poetry, history and philosophy. Naturally, with Greek authors as our primary sources, our modern view of this period is strongly Helleno-, particularly Athenocentric. The classical authors are largely silent about their northern neighbors, the early "Celts" -- surviving literary reports were written at great temporal and spatial removes, and are far from objective.

|

Model representing circulation of

Mediterranean imports. |

The Hellenization model derives to a great extent from the diffusionist historical philosophies of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and may be viewed as a direct descendant of Renaissance thought on the classical Mediterranean. Our history and our ideology of history grew out of familiarity with ancient Greek and Latin texts. Little wonder, then, that our slant on the period during which the ancient Greeks flourished is determined by how they saw themselves and others:

this is the idea that Greek culture was so inherently superior and attractive that 'barbarians' would naturally wish to emulate it whenever they had the privilege of being exposed ot it (Dietler 1995, 93)

To the Greeks, the "Celts" could be objects of ridicule (in comedy), of fear (as invaders), of exploitation (as mercenaries), and even of aesthetic appreciation (in art), but they were always and irreducibly barbarians. Post-Renaissance historians have adopted this view unquestioningly; of course, by modern standards, the lack of urban and state structures, and practices such as trophy decapitation of enemies, clearly mark the "Celts" as "barbarian ." Explanatory models have incorporated this judgment, often explicitly. A crucial element in a diffusionist model is the self-assessment of the acculturated group as inferior to the culture to be emulated; this is the motivation behind the acceptance and incorporation of "influence" from the higher culture. Pauli cautiously formulates the relationship thus:

It is particularly in the peripheral areas of higher-developed cultures that interchanges take place, which were not limited solely to material exchanges of goods and superficial assumption of ways of living. When the Greeks, and also Etruscans, saw the peoples of the North as barbarians, as strange cultures with curious customs and incomprehensible language, the latter, on the other hand, correspondingly felt a newly-awakened consciousness of otherness, an important basis for the formation of their "we"-group identity. (note 1 ; Pauli 1980, 22)

Insofar as this model suggests the crystallization of "Celtic" identity on the borders where interaction with other peoples took place, it is in accord with the theories of ethnic and cultural identity formulated by Barth and others. However, Barth's model is entirely free of the key element in the diffusionist model represented here by Pauli, namely that the "Celts" see themselves as "other" to the Greeks, as "barbarian" and thus in need of Hellenization.

We have reliance on a one-sided literary record to thank for this value judgment. For example, Diodoros is shocked at the exorbitant price "Celts" of his day would pay for a jar or even a cup of wine, attributing it to monumental lust for wine on the part of the barbarians (V.26.3; see Drinking). The record does not preserve the corresponding "Celtic" trader's shock that the Massaliotes would sell wine, an eminently marketable commodity, in exchange for such insignificant goods as servants or slaves (Champion 1989, 14). Diodoros's assessment is incredulous because it sees the situation from only the Massaliote trader's point of view, to whom wine was cheap and slaves expensive. It does not take into account the high prices the "Celts" undoubtedly demanded for the exotic wine; nor does it consider how cheaply the "Celts" held human life in general, reputedly being willing to submit to execution themselves in exchange for riches consisting of silver, gold and wine (Poseidonios, in Athenaeus IV.154.c). A complex situation is rendered almost a caricature, and thus it enters our historical reconstructions.

The diffusionist model goes further than the ancient sources in seeing the inhabitants of Iron Age Europe as an undifferentiated mass. To judge that the "Celts" saw themselves as "other" to the Greeks presupposes that they were not "other" to each other -- that the different groups shared a cohesiveness that united them vis-à-vis the Massaliote foreigners -- an assumption that is quite unfounded.

When we read that the "Celts" took on Greek "ways of life," it is important to remember that this idea is based on the presence of a few Mediterranean vessels in "Celtic" tombs. The interpretation of goods found in funerary contexts presents specific challenges that differ from that of goods in settlement, hoard, deposit or scattered contexts. Briefly, "Celtic" burial practices are quite different from those of the Greeks; they show no evidence of adoption (or even awareness) of Greek "ways of death." The "Celtic" funerary assemblages are placed within specially-built chamber tombs under tumuli; they clearly refer to death and the afterlife. It is highly questionable that they can tell us a great deal about activities practiced by the living. For example, the groups of vessels found in the burials have led to a pervasive assumption that the "Celts" imitated Greek drinking practices in the form of the symposion. There is, however, no archaeological or literary evidence that the "Celtic" Trinkfest took on any of the characteristics of the Greek symposion. Thus, imitation of the Symposion can be ruled out as a motive for the importation of Greek vessels. Similarly, the presence of wagons in "Celtic" tombs has been tied to the depictions of the ekphora on Greek Geometric vases -- a connection that lacks all chronological and causal coherence. Considering that the Greeks never buried wagons with their dead, emulation of that practice is an unlikely motive for the inclusion of wagons in "Celtic" tombs.

Underlying these models is the assumption that importation of Greek objects, motifs and styles was closely accompanied by the importation of Greek ideas. For an imported object to function as a carrier of meaning, ideas and cultural values, however, the receiving culture must associate and understand both the place of origin and the ideas being transmitted. We have no evidence that the ancient "Celts" so associated the Western Greek (South Italian) or Etruscan places of manufacture of nearly all imported luxury vessels with the archaic and classical Greek civilization (Dehn and Frey 1979). Furthermore, we have no way of knowing what "Greek" meant to the early "Celts." Lacking evidence that the "Celts" considered their imports Greek, or that they considered Greekness to be anything particularly special, we have little basis for the idea that the imports in question were carriers of ideas and institutions, providing Greek impetus for cultural and artistic change in Europe.

The diffusionist model is still clung to by those who "still believe that the sole historical function of the barbarians in the West and to the North was to wait passively for Hellenization and Romanization -- and presumably be glad of both when they finally came" (Ridgway 1992, 546-50). The German-language literature is still dominated by the psychological and socio-cultural argument of dependence and emulation, while the English-language prehistorians prefer to postulate an economic basis for "Celtic" acculturation.

Explanations of culture change generally take one of two stances. The evolutionary camp sees change as an internal development, while the diffusionists see change as a result of interaction with external groups. Diffusionist thought goes by many different names; my focus here is on the specific core-periphery models used to explain change in Iron Age Europe.

All such models are based on the designation of the Mediterranean as central, Europe as peripheral; "it has become common to speak of 'hellenization' or 'romanization,' as if such processes were natural, and Greece and Rome were naturally to be thought of as centres" (Champion 1989, 15).

Interregional interaction theory is currently an active field of anthropological inquiry (Schortman and Urban 1992); among the many approaches the core-periphery (or center-periphery) model has been particularly influential and long-lived (Champion 1989, 2 ff.).

In 1974 and the following decade, Immanuel Wallerstein formulated "world-systems analysis," a new method of explaining change within the world economy through analysis of the interactions between core, semi-peripheral and peripheral areas (Wallerstein 1974). Although Wallerstein explicitly stated that his model was only applicable to capitalist economies since the sixteenth century, his model was soon applied to pre-capitalist contexts as well. Schneider, among others, observed that Wallerstein's model underestimated the importance of luxury or prestige-goods exchanges (1977). With some adjustments, variations on the world-systems approach continue to be used in analyses of prehistoric and pre-capitalist economies (Chase-Dunn and Hall 1991, 5 ff.)

Mauss's groundbreaking 1954 Essai sur le don formulated the various aspects of the exchange of gifts within systems of reciprocity and obligation. Applied to Iron Age Europe, the model is used to explain the presence of spectacular Mediterranean imports like the Vix krater as "cadeaux diplomatiques" used to cement relationships between the local élite and their Mediterranean counterparts, or as gifts from foreign merchants who sought access to raw materials and slaves in the control of the local "princes" (e.g., Winter and Bankoff, 162 ff.). Once in the hands of the "Celtic" chieftain or "prince," they served the non-commercial function of "status-markers" within the higher strata of the local society.

Frankenstein and Rowlands based their model of culture change in Iron Age Europe on the anthropological concept of a prestige-goods economy. Their influential 1978 article considers the Hallstatt "paramount chiefs" to be entirely dependent on the importation of Greek luxury goods, for redistribution within their local economies. The imports brought about the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a very few members of the local élite who controlled both the trading contacts with the Mediterranean and the means of the accumulation of raw materials and surplus for trade. As a result, militarization and a highly stratified society with ever more exclusive dependence on the ostentatious display of imported status markers led to instability -- "Late Hallstatt society was so fascinated by the south that it got into a blind alley at the end of which self-destruction was waiting" (note 2; Pauli 1985, 35). When around 500 BCE, sea-going trade in the western Mediterranean was severely restricted by increased Carthaginian activity, the princely Hallstatt culture collapsed "like a house of cards" (Cunliffe 1988, 32).

Aspects of these models have recently been called into question. Renfrew suggested that "the simple assertion of the operation of a 'world-system' is sometimes little more than a reiteration of the old diffusionist model, ill-concealed in a new jargon which has replaced 'focal centre' or hearth (foyer de civilisation) with the new 'core,' and 'barbarian fringe' with 'periphery'" (1986, viii). With regard to Iron Age Europe, it is particularly the "picture of a Hallstatt system effectively controlled from outside, heavily dependent on the vagaries of Greek trade" that has been vigorously refuted in recent years (Arafat and Morgan 1994, 122). Analysis of the imported objects, their find contexts and the degree of acculturation to be observed in local archaeological sites led Dietler to question "Mediterranean interests or presence in west-central Europe" (1991, 136). Finally, the archaeological record reveals no drastic break but rather continuity at many sites from the Hallstatt into the early La Tène period, undercutting arguments based on chronological parallels between Greece and Europe.

A very promising new approach was formulated in 1986 by Renfrew and Cherry. Their peer polity interaction model examines the relationships between autonomous nearby socio-political units. By narrowing the focus to clusters of neighboring communities, it reveals structures and dynamics, not always of a competitive nature, within a cultural area. Champion and Champion apply the model to point out homogeneity in the material culture, warfare, settlement patterns and burial forms within the late Hallstatt zone; however, their consideration of the Mediterranean imports leads again to a dependency and house-of-cards conclusion (1986, 59-62).

At the current state of Iron Age European studies, workshops, let alone hands, economic centers, political structures and centers all have yet to be isolated and defined. Explaining regional trade and other interactions will be considerably eased once we can point out with confidence which objects were locally made, which were brought in from elsewhere,

The study of "Celtic" art has been profoundly affected by the dominance of diffusionist thought in the history of the field. From the beginning, early and mid-nineteenth-century discoveries of what we now call "Celtic" finds were variously considered Roman, Teutonic, British, Germanic, Helvetian, Italic, Gallic, or "Celtic" . "During the Second Empire the finds were attributed, according to the whim of the moment, to the Gauls or to the Romans" (Favret, quoted in de Navarro 1936, 302).

As late as the 1880s , Ludwig Lindenschmidt, prolific publisher of the Antiquities of Our Pagan Prehistory (Die Altertümer unserer heidnischen Vorzeit), was "still imprisoned by the shackles of a conviction that no barbarians were capable of producing masterpieces of craftsmanship, and so ascribed to the Etruscans the material now recognized as La Tène Celtic metalwork" (Megaw and Megaw 1989, 13).

Lindenschmidt was an exception; increasingly, nineteenth-century archaeologists and prehistorians came to recognize the distinctive qualities of the "Celtic" finds. Acknowledgement that the "Celtic" works were locally produced did not, however, lead to appreciation of their style. Instead, the focus shifted from trying to attribute all finds to the Mediterranean to discovering Mediterranean influence in the European works. Excavations that unearthed imported vessels from the Etruria and Greece played a large role in this quest. Déchelette's monumental 1927 Manuel d'Archéologie Préhistorique attributed sixth-century advances in barbarian Europe to the increasingly profound exertion of the "fecund influence of the great currents of the southern civilisation" (note 3; 1927, III:2). Early La Tène art he termed "half-barbarian," since it would have remained stuck in monotonous repetition of geometric motifs had it not been for the impetus of Greek influence. As it was, the remarkable progress in La Tène style was fueled by "imitation of certain motifs of archaic Greek ornament" (note 4; 1927, III:3).

Before Jacobsthal's groundbreaking study of Early Celtic Art, there was no doubt of the primacy and superiority of Greek art: "Celtic art was generally viewed from a classical standpoint and regarded as a degenerative derivative of southern art" ( de Navarro 1936, 319). Jacobsthal's exhaustive knowledge of Greek ornament and his discerning eye enabled him to discriminate what was original and un-Greek about "Celtic" art, and to trace indigenous stylistic developments within the framework well established in Déchelette. Despite his appreciation of "Celtic" creativity, however, Jacobsthal, steeped as he was in the classical tradition, lamented that the "Celts" were not more strongly influenced by Greek imports: "they did not decide for Greek humanity, for gay and friendly imagery: instead they chose the weird magical symbols of the East" (1944/1969, 162). His verdict on "Celtic" art expresses the deep ambivalence of the classical archaeologist confronted with an art contemporary with but alien to the familiar classical repertoire, and resistant to conventional Western interpretation:

their art also is full of contrasts. It is attractive and repellent; it is far from primitiveness and simplicity, is refined in thought and technique; elaborate and clever; full of paradoxes, restless, puzzlingly ambiguous; rational and irrational; dark and uncanny -- far from the lovable humanity and the transparence of Greek art. Yet, it is a real style, the first great contribution by the barbarians to European arts (1944/1969, 163).

Jacobsthal's recognition of the place of early Iron Age "Celtic"

art in Western art history has been little heeded. Subsequent surveys

have treated it, if at all, as a blip on the radar screen of the

linear progression of the classical tradition; as one of several

barbarian aberrations (e.g., Honour and Fleming 1991, 136-137) or as paving

the way for later, more significant Christian-era developments

(note

5). Fortunately, such perceptive and enthusiastic scholars as the

Megaws

have recently devoted entire volumes and lengthy studies specifically

to the arts of Iron Age Europe, fanning the flames of the current

wave of Celtomania, but still largely disregarded by classical art

historians. The dominant model continues to be that of a

"Kulturgefälle" between the "Hochkulturen" of the

Mediterranean and the barbarians of Europe.

This model is perpetuated, neither

as a modern construct borrowed from ancient Mediterranean authors and

cemented by centuries of classical orientation in the Western

ideology of history, nor as a value judgment based on subjective

criteria, but as an actual fact of history with both descriptive and

explanatory force.

model is perpetuated, neither

as a modern construct borrowed from ancient Mediterranean authors and

cemented by centuries of classical orientation in the Western

ideology of history, nor as a value judgment based on subjective

criteria, but as an actual fact of history with both descriptive and

explanatory force.

It is not surprising, then, that "Celtic" art histories almost uniformly begin with the dying Gaul, a Roman copy of a Greek original of third-century BCE Pergamon. The life-size figure was part of a political monument celebrating victory over the barbarian foe. The compelling quality of this gorgeous image seduces the viewer into forgetting that it is not a very objective portrayal, and tells us less about the "Celts" than how the Greeks, and by extension we, see them.

This Hellenocentric history has left its mark on the study of "Celtic" art in three major forms:

Striking examples of this trend include the interpretation of the fortification wall at the Heuneburg, which "must" have been constructed with the collaboration of a Greek architect; and the Hirschlanden warrior, who is "unthinkable" without, and may allegedly have been cut from, a Greek kouros. The burial of wagons in "Celtic" tombs has been "explained" as an imitation of the Greek Ekphora, thus attributing an entire class of vehicles to Greek influence.

What Boardman calls "the assimilation of classical debris" (1994, 306) is frequently observed on "Celtic" bronze flagons. Indeed, the very shape is credited to Etruscan prototypes, themselves derivative of Greek vessels. The figural motifs of heads or beasts are traced back to the handle attachments of Greek and Etruscan vessels. Although Lenerz-de Wilde and others have shown that the principles of composition underlying the non-figural motifs are based on compass-drawn geometries entirely different from Greek floral anthemia, the former are still often considered to be direct descendants of the latter (see 3.).

The discussions of the nine drinking horns found in the Hochdorf burial, for example, have not focused on the obvious questions: why are there nine? are they in the tomb for use in the afterlife, and if so, by whom? what role did they play in banquets amongst the living? Instead, several exhaustive treatments have addressed the interpretation of the material in light of the traditional question of derivation: did the "Celts" derive their drinking horns directly from the Near East or Eurasia, or was the practice adopted in emulation of the Greeks? (see the "Celtic" Trinkfest).

The same is true of interpretations of motifs in "Celtic" art. Since Jacobsthal, "Celtic" art history has resembled a tug-of-war between those advocating eastern sources and those who see only Mediterranean influence. The third source, indigenous tastes and traditions, has received rather less attention.

|

|

Frey and Schwappach 1980; 339 |

Juxtapositions of superficially familiar forms are strongly persuasive, creating the impression of a direct line of descent. Lotus-palmette friezes of Caeretan hydriai of about 525 BCE are considered the direct antecedents of "Celtic" openwork patterns, notably the gold foil cup from Schwarzenbach and the Eigenbilsen drinking horn foil of ca. 400 BCE. When we compare the actual pieces, or at least color photographs of the objects, rather than line drawing, of course, we note the colors and materials, the subsidiary placement of the ornament on the hydria, and the sculptural quality of the foil. The gold openwork pattern consists of fully-formed and unmistakably "Celtic" elements. There are no intermediate pieces showing a process of reduction and transformation. As Jacobsthal observed in 1944, "again and again we hit on the same enigma: Early Celtic art has no genesis" (1944/69, 158). In other words, there is no period of apprenticeship, of imitation, assimilation and gradual separation into a distinct style.

Blossom-palmette friezes. Frey 1980,

fig. 14 Comparanda:

Reconstructed gold foil ornament originally applied on cup of organic material (?). Found at Schwarzenbach (Germany). |

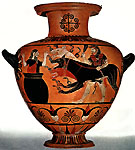

Black figure hydria, ca, 530-525 |

Detail of gold foil ornament band, drinking

horn, found at Eigenbilsen (Belgium). |

The aesthetic and repertoire are strikingly reminiscent of the

arrangements of teardrop and comma shapes, the bands of linear

ornament, and the surface articulation observed in the gold foil

ornaments added to the

Kleinaspergle

drinking cups. Typical early La Tène

motifs are arranged on the interior and exterior of two

imported Attic kylikes without regard to the original Greek vase

paintings. Analysis of the foil pieces, abstract teardrop shapes and

circles, reveals that the floral ornaments of the kylikes and the

figural scene were neither imitated by the "Celtic" artisan, nor

adapted in any way. Indeed, the Attic elements were entirely ignored

in favor of local abstraction, handling of material and style that

would have been entirely foreign to the Athenians who made the cups.

are arranged on the interior and exterior of two

imported Attic kylikes without regard to the original Greek vase

paintings. Analysis of the foil pieces, abstract teardrop shapes and

circles, reveals that the floral ornaments of the kylikes and the

figural scene were neither imitated by the "Celtic" artisan, nor

adapted in any way. Indeed, the Attic elements were entirely ignored

in favor of local abstraction, handling of material and style that

would have been entirely foreign to the Athenians who made the cups.

1, 4, 6: Ornaments in Greek Red Figure vase painting.

2: Bern-Schoßhalde silver fibula.

3: Dammelberg torc.

5: Sanzeno sword scabbard.

7: Bussy-le-Château (France) torc.

Frey 1980, fig.

22

The line drawings of motifs on "Celtic" objects conceal from us

differences in scale, materials, types and functions of the objects

themselves. A comparison drawing of a very common type is represented

here by Frey's 1980 Fig. 22. Presented side-by-side

are, in the top row, a Greek motif and a "Celtic" fibula detail; in

the second row, a detail from a torc beside a Greek motif, and on the

bottom a Greek motif beside a "Celtic" torc detail. This arrangement

seems to speak for itself, but is confusing upon close examination.

One must turn to the captions to discover the types and origins of

the objects. The "Celtic" examples are identified, but "Ornaments in

Greek Red Figure vase painting" gives no specifics as to date, place

of manufacture in Greece or Italy, vase type, placement of ornament

on vase, or whether any Greek vases with ornaments of this kind were

actually found in "Celtic" contexts. Nevertheless,

Frey

writes that "there is no doubt that the continuous wave tendril is to

be derived directly from Greek motifs"

(note 6,

1980, 85).

The Besançon flagon is an Etruscan import found in France. It, too, presents us with an example of a Mediterranean object that was physically in the hands of a "Celtic" artisan, allowing us to observe any direct influence that may have taken place. The ornaments incised into the bronze by the Celt include a palmette-like motif that echoes the handle attachment's form in an entirely new fashion. The rest of the vessel is covered with swirling yin-yang circles, teardrop commas and other purely local motifs that contrast jarringly with the simple, rigid Etruscan palmette.

An inescapable conclusion emerges. Although the local craftsmen handled, repaired and embellished objects imported from the Mediterranean Hochkulturen, they were apparently not over-impresssed; their own style is in no way altered or diverted by any southern "influence." If anything, the local pieces may be read as an explicit rejection of Mediterranean illusionism and figural narrative. When a foreign motif or stylistic element was introduced into the "Celtic" repertoire, it was immediately and unmistakably appropriated into the "Celtic" artistic language. Thus, zoomorphic creatures, floral elements, geometric aptterns, disembodied heads or vessel forms do not undergo any lengthy transition from copy to adaptation to transformation. When such an element appears in "Celtic" art, whether inspired by an import or not, it appears in "Celtic" style.

More interesting, perhaps, than the short list of imported motifs is the enormous range of Mediterranean interests that clearly held no attraction for the "Celts" and were consistently rejected in favor of local priorities. The historian may ask why the "Celts" refused to write down their stories, or why they did not build monumental stone architecture. The art historian notes the rejection of figural, narrative art, of illusionism, and of the logic of Greek floral and geometric ornament in favor of abstraction, stylization, dismemberment and curvilinear ornament that denies distinctions between foreground and background. "Celtic" metalwork is highly sculptural, while retaining linear articulation, rejecting the classical Greek striving for integration of sculptural form and surface. "Celtic" pottery is never decorated with narrative figural scenes; instead, its ornaments are polychrome and textural. In short, "Celtic" producers and consumers alike neither perceived an inferiority or lack in their own fully developed stylistic and craft traditions, nor did they look to the Mediterranean as the "center" from which artistic influences were to be imported.