|

Marginal Landscapes

As Critical Infrastructure: Boston's Back Bay Fens

Kathy Poole

Published in the Proceedings of the

Annual Meeting of the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture,

Los Angeles, CA, 10-14 April 2000. Copyright Kathy Poole, all rights reserved

Abstract

Urban landscapes have particularly important roles in the continuous project

of building the city. Landscapes, as evolving infrastructures, take on

various forms, functions, and dynamics in relation to the surrounding

city. They embody expressive relationships that mirror changing cultural

relationships between nature and city. They are physical relationships

with a potentially powerful role in structuring the city. They are social

relationships that demonstrate the value of infrastructure in making places.

The essay explores these potentials through the infrastructure of a park,

Boston's Back Bay Fens, an exemplar in urban design, civil engineering,

and landscape architecture. It departs from others' consideration of the

Fens as an infrastructure at a singular moment in time, when Frederick

Law Olmsted designed it and guided its construction to his vision. Instead

the essay considers the Boston landscape throughout its life as an urban

landscape, from its relatively unmanipulated 1775 marshland form to its

current debates. As a case study, the Fens has expressed a wide variety

of attitudes regarding the relationship of the city to both infrastructure

and nature.

The essay's intention is twofold. First, it seeks to expand our repertoire

of how designed urban landscapes, as built natural infrastructures, can

contain dynamic and powerful potentials for contemporary urban design,

particularly in their ability to continually reinvigorate citizens' understandings

of their places within the city. Second, it seeks to demonstrate how "evolutionary"

infrastructures have a unique ability to accommodate changing populations,

particularly marginalized groups and expressions that have no other place

within the designed city.

Landscapes as Evolutionary

Infrastructures

Landscapes like parks and public squares are more than important elements

in the city. They are infrastructures, basic components of urban living,

elements necessary to accommodate congregated living. One of the ways

that landscape infrastructures are most important is their ability to

evolve over time, to take on various forms, functions, and dynamics in

relation to the surrounding city. 1 They embody expressive relationships

that mirror changing cultural relationships between nature and city. They

are physical relationships with a potentially powerful role in structuring

the city. They are social relationships that demonstrate the value of

landscape infrastructure in making places.

As evolutionary infrastructures capable of assuming numerous roles, urban

landscapes are critical to the continuous project of building cities.

This essay demonstrates these potentials through Boston's Back Bay Fens,

an exemplar in urban design, civil engineering, and landscape architecture.

The investigation considers the Boston landscape throughout its life as

an urban landscape, from its relatively unmanipulated 17th c. marshland

form to its current debates.2

The contemporary Back Bay Fens area of Boston is a remnant of the original

fen that encompassed over 1000 acres.3 Boston's original fen was a tidal

wetland that also received drainage from three water bodies: the Muddy

River, Stony Brook, and the great Charles River. The bay both separated

and joined the bulbous head of Boston from Cambridge and Roxbury and South

Boston, the latter connected only by a thin sliver known as The Neck.

This essay considers not only the infrastructure roles of the built landscape

of the park but also the roles of the park land–the Back Bay Fens

landscape in all its forms both preceding and post-dating the construction

of the park proper.

The Fens evolutionary story expands our repertoire of how built natural

infrastructures, can contain wide-ranging, powerful, and creative potentials

for contemporary landscape design, particularly in landscapes’ abilities

to continually reinvigorate citizens' understandings of their places within

the city. The Fens also demonstrates how "evolutionary" infrastructures--—infrastructures

whose expressions change over time—have a unique ability to accommodate

changing populations and accommodate the increasing diverse populations

of the city, particularly marginalized groups and expressions that have

no other place within the designed city.

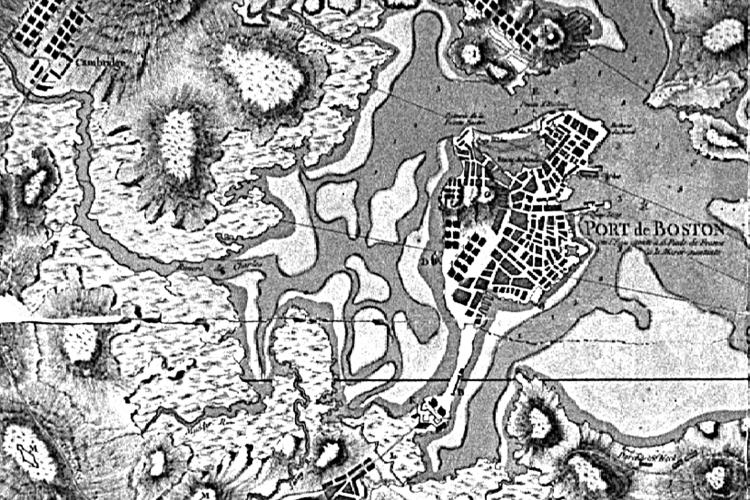

Fig. 1. Boston in 1775. Carte du Porte et Havre de Boston, Chevalier de

Beu_rin (Courtesy Harvard College Library Map Collection).

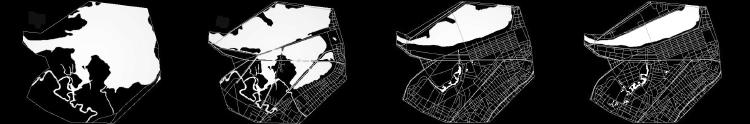

Fig. 2. Back Bay’s evolution over time.

Wild Territory (-1802)

In 1630 Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes described the marsh landscape of the

Great Bay (as it was called) as an overgrown tangle of windblown trees,

filled with an array of wildlife and "one human."4 It was murky

territory, ambiguous land that was not quite land but not quite water.

Subject to diurnal tides, it literally shifted beneath people's feet,

making it quite undependable. This murky territory was proximally near

the "owned," platted, and bustling territory of central Boston.

Yet, conceptually, it was a world away. In fact, most accounts of it are

'remote'–from somewhere else–reporting it as a place that colonists

liked to view passively.5

The coupling of expansiveness and uncontrolability imprinted Back Bay

as a place of untamed, wild creatures that could only do colonists harm.

Some of those wild creatures were human. It kept French and English troops

literally 'at bay' in their military encampments. Nonetheless in April

1775, the British attempted to capitalize on the Bay's murky, shrouding

qualities when they crossed the Charles River portion of the bay, prompting

Paul Revere's famous cry that "the British are coming."6

The fens’ wild qualities also allowed the marsh landscape to serve

important infrastructural functions. As a shifting landscape that could

not be (literally) settled, it allowed only transitory human inhabitance,

primarily men whose intents were to catch those wild creatures, "the

haunt of duck hunters, [and] fishermen" as well as "mudlarking

boys," children who enjoyed frolicking in the mud.7 For approximately

a century and a half, it served as a version of the increasingly popular

‘urban wilds,’ those remnant landscapes within the city that

maintain access to the city’s former nature, a natural landscape

not filled with human intention.

The marsh’s wildness also bolstered the city's conceptual understanding

of itself. Functioning as a reciprocal to the built city, the fens made

distinct the sense of the city as a 'cultured' entity and not a savage

territory that the British accused it of being.

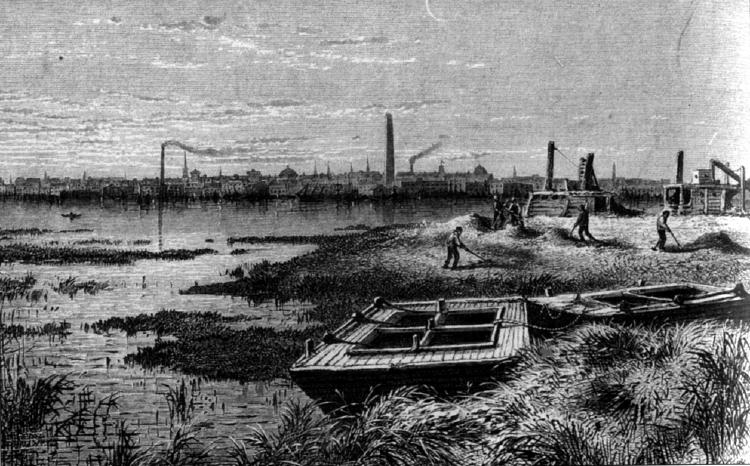

Productive Landscape (1803-1821)

By 1803 growing land availability pressures of Boston took precedence

over impressions of the land being dangerous territory–at least in

part. Few took up residence in the low lands, but land-poor colonists

began looking for free ways to raise livestock. The Back Bay's marshy

lands, adjacent to the traditional grazing land of Boston Common, made

them obvious choices, particularly once grazing was banished from the

Common. The marsh lands were also obvious choices because they were filled

with salt hay. In such a vast marsh, cows grazed freely without danger

of outcompeting one another and without the need for cattle owners to

own land. When it was time to slaughter, the owners simply went out to

'hunt' them.

The marshes were also valuable hay crops for those whose land was not

large enough to support hay feed for their animals. Citizens need not

own this crop land. They merely needed to load hay on gondolas from the

bay and on carts from landside. And finally, increasing numbers of Bostonians

fished and dug clams for subsistence and for sale at the market.

Therefore, during the early years of the 19th century, the Back Bay landscape

shared oftentimes forgotten values of urban landscapes. It supported productive

citizens in positive ways that not only served them personally but also

served the larger city. The landscape's activities had no direct economic

benefit to the city's official economic tally, what might metaphorically

be likened to a ‘gross national product.’ Nonetheless, the landscape

served the city well by contributing to the city's less official but perhaps

more important ‘gross urban product.’ By supporting the subsistence

of residents, it contributed to Boston's economic stability.8 It was a

productive landscape that did work for the city's developing urbanity.

Fig. 3. Salt hay harvesting in the marsh.

Unsanctioned Activities (1821-1849)

The productivity of the fens landscape grew exponentially with the 1813

actions of Uriah Cotting and his business partners when they petitioned

for "liberty to build a Mill Dam."9 The fifty foot wide causeway

was composed of a gravel toll road along the river side and on the bay

side was a plank walk planted with poplars. A short cross dam divided

the bay in two. At high tide water passed through floodgates, moved through

sluices, and generated power as it passed into a receiving Basin. At low

tide, the water drained back through Mill Dam sluices into the Charles

River. The industrial mecca anticipated by Cotting never materialized,

in part because the anticipated tidal energy proved highly overestimated.

The greater reasons were the railroads that came in 1835. The Boston +

Worcester and the Boston + Providence converted the "waste"

land into an important transfer station for goods. Soon the Back Bay was

a bustling industrial complex.

Intentional, physical public access–as opposed to mere visual access–subdued

some of the landscape’s wild associations and brought new infrastructural

possibilities. People began to enjoy being in the marsh. People cut ice

from the shallow marsh waters. The Mill Dam became a fashionable place.

People promenaded. Irish immigrants by the hundreds enjoyed big rigger

boat races from along the Mill Dam.10

Simultaneously, the marsh continued to retain its 'wild' qualities, albeit

subdued, and therefore allowed unsanctioned activities to occur without

retribution. The marsh landscape hosted activities that could not occur

in more codified and behaviorily restricted urban landscapes. And it harbored

urban needs and citizens that the built city could not. Contemporary accounts

report that a walk on the Mill Dam meant that couples could court in the

early evening hours without fearing observation.11 And the Mill Dam's

breadth, length, and straight run made it a favorite place for sleigh

racing, impossible on city streets. Small tipcarts dumped household garbage,

while others hoed through the ashes and took away chairs, bottles, and

other "unconsidered trifles."12 Trash dumping enabled some citizens

to rid themselves of unwanted rubbish while other citizens gathered what

they needed. And finally, the marsh took on a long lasting marginal activity

when in 1827 the city obtained permission to flush sewage into the fen.

Functionally the tides' natural flushing took the waste out to deeper

waters, helping stem the city's cholera outbreaks–at least to a degree.

Urbanistically the fens landscape became an official municipal utility,

a sewage infrastructure.

The fens were no longer a reciprocal landscape to the city. The marshland

had established a median ground, a wonderfully ambiguous landscape infrastructure

that could hold many expressions and serve many urban infrastructure needs.

Fig. 4. "Waste" land becoming integrated with the city (Courtesy

Boston Public Library).

Coordinated Infrastructures (1850-1869)

Within ten years of the railroads' coming, the ever increasing quantity

of sewage and the ever decreasing tidal flushing caused citizens to continually

complain of "the abode of filth and disease" from which "every

western wind sends its pestilential exhalations across the entire city."13

Feces rested on these flats at low tide. A simmering public movement for

sewage reform heated to a boil.

The sewage reform issue deserves a more thorough treatment than can be

accommodated here. It suffices to say that the Boston Board of Health

concluded that the "mills were of little profit to anybody and nuisance

to everybody...and that it was desirable to fill the Receiving Basin...and

to convert it into solid land."14 The City negotiated a tripartite

agreement between the Commonwealth, the City, and two corporations. They

developed a plan and began filling land at a frenzied pace. All totaled,

they filled over 800 acres, an unprecedented urban design effort.

Based on Haussmann's and Alphand's Parisian infrastructure efforts, Back

Bay was transformed into a particularly well-orchestrated and unified

collection of infrastructures– an impressive urban design effort:

evenly-distributed, planned streets, orchestrated topography, positive

surface drainage, understandable lot layouts, street trees, a park-like

boulevard, sculpture, and a set of deed restrictions to ensure its 'proper'

development.

The prescriptive urban design came with a social cost. Forty of what John

Charles Olmsted called "the cheapest kind of dwellings" were

condemned. He continued to say that unless some extensive and expensive

improvement of the whole valley were to be soon made, it was seemingly

inevitable that this "squalid and unsanitary occupation of it would

cover all parts of this valley and discourage good occupation of the neighborhood."15

Both turn of the century and contemporary writers have referred to these

citizens pejoratively as "squatters" and their dwellings as

"squalid shacks" and "shanties".16 However, a closer

inspection of period images suggests that the dwellings were merely typical

of most 18th century Americans. These Bostonians, pejoratively called

"marsh people," were ordered out to make way for Boston's new

fashionable and elite neighborhood. Socially and financially more endowed

citizens took the places of the "marsh people" who were financially

unable to remain unless they were able to secure positions in the Back

Bay residents' houses as servants or other service personnel. Randomly

placed wooden houses and vegetable gardens were traded for unified, deed

restriction-bound brownstone walkups and tree lined boulevards. Where

Back Bay had earlier accommodated a variety of activities and social classes,

it was now a unified urban design, as one 1872 visitor nicely summed it

up, " a class environment of an unusually homogenous kind."17

Civic Infrastructure (1869-1882)

The populations of Stony Brook's watershed had increased so dramatically

that the City Board of Health's annual report speculated that "there

is not probably a foot of mud in the river, in the basins...that is not

fouled with sewage."18 In heavy rains sewers backed up into residents’

houses. Plus, the openness of the vast bay, much loved by many Bostonians,

was quickly becoming filled with four and five story buildings that threatened

to obliterate the city's intimate relationship with the natural landscape.

In 1869 prominent citizens and business people petitioned Boston City

Council to take lands to preserve unbuilt landscapes within the city by

making them parks. The desire for maintaining open space and solving the

sewage problem coalesced into a unique synthetic infrastructure solution

for its time, a stormwater park, a public landscape infrastructure concerned

with aesthetics that also provided important municipal services–flood

control and a kind of sewage ‘treatment.’

The City of Boston hired Frederick Law Olmsted to design Back Bay Park

(later to become the Back Bay Fens) to fulfill its unique specifications

for a park (which would have been linked to stormwater no matter who designed

it). As others have argued, Olmsted designed "ecologically"

by reconstructing the biotically degraded fen. But more importantly, Olmsted

wanted to maintain the full aesthetic, the complete sensibility of the

former fens landscape–its expansiveness, the waving of the marsh

grasses, the blustery winds, the tidal flux. His landscape embraced citizens'

memories as well as the site's ecological memory. The design was no mimic

of the historical landscape. It was clearly transformed into a contemporary

urban expression. What Olmsted delivered was a landscape rooted in the

history of the city and its collective memory.

It was not a cultured park aesthetic of the 19th century elite. Rather,

it was a ‘common’ one, an ordinary landscape of flat land and

marsh-like plantings. It was a landscape valued by 200 years of ordinary

citizens. As such Olmsted chose an aesthetic expression that enhanced

the project's ‘urbanity,’ a landscape design that is meaningful

to all residents, regardless of social class, and a design that contributed

to citizens’ understandings of the entire city.

Fig. 5. Transformation of ecological memory into urban expression (Courtesy

Olmsted National Historic Site).

Municipal Utility (1888-1901)

Because of the creative conjoining of park and stormwater utility, the

Fens functioned as everyone had intended. Stony Brook was encased in two,

9' rubble stone tunnels; the brook was then diverted through a gatehouse

just as it reached the Fens and channeled into a 7' brick bypass conduit

that released it into the Charles River. The Muddy River’s dry weather

flow supplied the Fens’ water; but in heavy rains, a gate valve allowed

it to be diverted through its own bypass tunnel to the Charles River.

Thus, only diluted sewage entered the Fens, and the Fens effectively functioned

as a storage basin for stormwater for the Back Bay area. But the city

grew, and soon the Fens was overwhelmed with sewage. Consequently, the

city built the Commissioners Channel, a new channel and new bypass channel

that would avert sewage being discharged into the park.

The problem was that the city constructed the Commissioners Channel before

constructing its link to the bypass channel. Raw daily sewage flowed into

the Fens for two years until it was diverted to the Stony Brook bypass

conduit in December 1889. Plus the Fens was used on numerous occasions

as a temporary holding tank for dewatering sewage- and deposition-laden

portions of the marsh that were being filled for development.

So distasteful were the conditions that the boats introduced in 1896 were

not-surprisingly removed in 1901 because of "lack of patronage,"19

a sentiment echoed in accounts of people avoiding the park. By 1901 the

Fens was transformed from being primarily a park landscape that also functioned

as flood prevention to being a municipal sewage landscape that hardly

functioned as a park.

It is true that the city chose a plan of action that would allow the Commisioners'

Channel to remain unfinished for eight years. It is also true that the

city chose to intentionally tarnish what had been a very expensive public

landscape works, 85 million in today’s dollars. Yet, these actions

reinforced the landscape’s ability to accommodate perhaps its most

marginal infrastructure, sewage. And at least for a time, it helped citizens

better understand the workings of the city—in all their aspects both

pleasant and putrid.

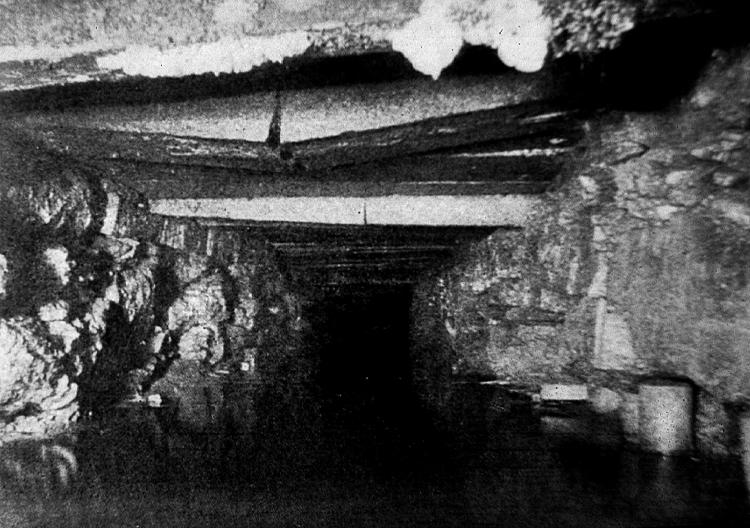

Fig. 6. Conduit beneath Back Bay Fens for sewage and storm waters.

Institutional Magnet (1901-1928)

Once a clear solution for the sewage problem was defined, the Back Bay

Fens became a magnet for a number of prestigious corporations that then

occupied its periphery: Massachusetts Historical Society, Isabella Stewart

Gardner Museum, Simmons College, Emmanuel College, Wheelock College, and

Forsyth Dental Clinic. 20 The two most notable were Boston Museum of Fine

Arts and Harvard Medical School both of which successfully lobbied the

city to redesign the park so that their buildings were "in closer

relation with the Fens."21 To be a part of the Fens was an asset.

Thus, park and institutions were conjoined.

So conjoined were they that residents and administrators began to complain

of the Fens' "misshapen," "ruined," and "overcrowded"

trees that (according to Olmsted, Sr.’s stepson John Charles Olmsted)

were not appropriate among $100,000 buildings.22 The Parks Department

began to replace Olmsted's semi-native, marsh-like choices to those more

likely found in traditional gardens and tidy up the waterway's scruffy

edges. And once the dam was constructed on the Charles River, the Fens

was no longer tidal, prompting administrators and designers to completely

realign the Muddy River, the water course that structured the Fens.

As partner to the institutions, the Fens still fulfilled desires and activities

specific to parks. But to some degree, it was relegated to being a mere

foreground to the institutions, a stage setting for the institutions that

comprised the main events. The Fens began to operate less as a field of

conceptual substance in its own right and more as null ground–open

space–into which other things were inserted.

One of those things was a series of active recreational fields. And another

of those things was garbage. In essence, the city accomplished its recreational

infrastructure goals through another urban infrastructure–landfilling.

The marshes were filled with excavated material from various subway construction

projects, a combination of coal and wood burning ashes, common city garbage,

and "old boilers, bricks, and up-rooted plumbing,"23 Just as

it had in the 18th c., the park served the larger city by providing a

place for it to cheaply dispose of unwanted excavation material, ashes,

and rubbish. A highly visible, upscale urban infrastructure of a park

simultaneously fulfilled a marginal infrastructure need of waste disposal.

Grounds for Collective Civic Expression (1929-1950)

In 1929 Bostonians quit filling the Fens with garbage and instead began

filling it with expressions of civic ideals. The first of these expressions

was the Fens Rose Garden. Its archways and brocade treatment so expressive

of the city's valuing of public gardens that it was more than doubled

to its present size three years later. The Victory Gardens site was a

playfield until WWII when the federal government launched a campaign supposedly

aimed at stemming a potential food shortage and investing people personally

in the war effort. The result was Boston’s expression of its patriotism

in the form of the Victory Gardens much as we know them today. Boston’s

more codified war memorials took form in the 1949 polished granite monument

that remains today. Citizens have continued to add monuments since: the

Korean War and the Vietnam War (1989); the Temple Bell (a peace offering

from Japan); monuments to sports heroes like Roberto Clemente; and famous

citizens like John Everett (a pilgrim forefather) and Katherine Bates

(writer of the poem that became the revered alternative American anthem

"America the Beautiful").

The point is that originally the Fens' primary aesthetic vision was of

one man, Olmsted. Yet, once his vision was literally overturned in the

earth, the Fens became a ground for a collection of civic expressions,

a place for Bostonians to display a series of values that the city as

a whole understood about itself.

Fig. 7. Rose Memorial Garden foregrounding Boston’s Museum of Fine

Arts (Courtesy Boston Public Library).

Displaced Landscape (1950-1982)

By the1950s the larger Back Bay area was an eclectic collection, too.

It included hospitals, movie theaters, concert halls, music conservatories,

women's colleges, religious colleges, art museums, historical societies,

and corporate 'institutions' like the Seagram Company and Fenway Park.

The businesses and residents were just as diverse. Leonard Bernstein lived

among hardware store owners, and soon-to-be famous artists lived near

prostitutes.

But in the1960s many of the same institutions threatened the healthy diversity.

The economic dynamics are fascinating but too complex to thoroughly examine

here. Suffice it to say that the burgeoning of tax exempt institutions,

large scale urban renewal efforts in the name of ‘progress,’

and a nationwide exodus to the suburbs caused Back Bay to lose much of

its middle class, an important stabilizing force for the neighborhood

and caretaker group for the park.

The result was the influx of new populations. Those without the money

to patronize drinking establishments turned to the Fens as their outdoor

bar. One cleanup effort resulted in the collection of ten thousand beer

cans, but this reportedly did "not even scratch the surface."24

Plus, lack of maintenance allowed homeless people to 'construct' dwellings

within overgrown shrubberies and inhabit unkempt, unused buildings like

the Clemente field house.

Phragmites, an aggressive dense-growing reed, was introduced in the Fens

sometime in the 1950s or 1960s to provide a nesting area for ducks. By

the 70s it was so visually impermeable that it provided a habitat of sorts

for a new displaced group–homosexual men. Since then gay men have

cruised the Fens looking for companions. Some men are looking for very

short term relationships, which occur in the phragmites, which is 25’

high and 30’ deep along parts of the Fens waterway. The vegetation

is so dense that the Fens now has a complex of 'sex rooms.' Many of these

men are married or others who do not want to reveal their homosexuality.

The landscape provides an opportunity for men to show themselves locally

yet cloak themselves from the rest of society—a precarious yet functional

balance. 25

Olmsted had always meant for the Fens to be a place of "persons brought

closely together, poor and rich, young and old, Jew and Gentile."

26 He got more than his wish in the 70s when the Fens provided some groups

a sort of refuge from the social mores of the majority. As a social infrastructure,

it offered the city a landscape for those who did not have another place

within the city.

Fig. 8. ‘Sex Rooms’ in the Back Bay Fens.

Repository of History (1983-1996)

Back Bay mounted a recovery in the 1980s. 'Recovery' was a key concept

for a park that was in such a degraded state. Bridges, walks, and buildings

were literally crumbling. Vegetation was overgrown and noticeably untrimmed.

Much of the original diversity had been lost, particularly the understory

trees and shrubs. Volunteer and invasive plant species confused the park's

aesthetic. And drainage was uncontrolled.

Sparked by a resurgent interest in landscape history and in Olmsted himself,

the plan helped garner a constituency which spurred the State Legislature

in 1983 to call for "the preparation of plans...and for the rehabilitation

and restoration of the Olmsted parks in the Commonwealth," including

the Back Bay Fens.27 And the position of restoration is still the strategy

in effect, best described by Pressley Associates/Walmsley Associates'

1983 plan, in which they propose that the Fens' strategy be one of "Adaptive

Restoration... the accommodation of new [post-Olmstedian] uses while preserving

the "look" of the original scenic composition."28 Apparently,

the Fens is a valuable infrastructure as a historical repository of many

times and values and expressions–a pastiche of the city’s history.

Making Cities

With this plan still operating as a conceptual guide, the Fens has steadily

been improved since the 80s. But its pivotal moment is now. Together active

citizens groups, the Parks Department, Boston Water and Sewer Authority,

and other municipal authorities have landed a $19 million+ coup and secured

approval for the Fens to be dredged and its banks regraded. With this

effort, Bostonians have the chance to exercise urban design in ways that

we should perhaps all be exercising.

The Back Bay Fens demonstrates how expanding public landscapes’ roles

can accommodate the increasing diversity of urban populations. It has

continually accommodated–even nurtured–citizens, activities,

and social conditions that have been unwelcomed and shunned by more codified

and restrictive built landscapes: becoming recycling territories; housing

those without property; offering workplaces and food sources for those

without conventional employment; sheltering homeless displaced by more

restrictive politics; providing cover for socially shunned citizens; accommodating

a diverse population not as actively fostered elsewhere in the city; and

providing a welcomed territory for typically disdained municipal infrastructures

like sewage treatment, stormwater control, and landfilling. And only in

rare moments has accommodating these marginal roles disallowed or diminished

more codified activities and populations that are accepted anywhere in

the city.

The Back Bay Fens also demonstrates how built natural infrastructures

can further citizens’ understandings of the city: the municipal services

and urban processes that make it work; the values it holds collectively;

the relationship of those collective values to those that are outside

mainstream mores; and the range of relationships to nature from contrast

to it to foreground for it. To find these creative intersections expands

not only the city’s aesthetic expressions but also provides more

forums for citizens to exercise more aspects of their citizenship.

And finally the Back Bay Fens also demonstrates how landscapes, as marvelously

amphibious structures, landscapes able to transform themselves into new

structure that serve the city's changing needs. The Fens' evolution demonstrates

the value of shifting our view of designed urban landscapes from being

static infrastructures conceived at a singular moment to being dynamic

urban structures that can continue to be active agents in the city.

Were the city to value the Fens’ legacy of continually providing

a place for that which the city rarely gives place, it might allow one

of the Fens’ most important histories to resonate into its future.

Were the city to ensure that the Fens’ future designs continue to

enrich citizens’ understandings, it might continue to offer creative

models of urban design. Were the city to value the Back Bay Fens’

ability to continually evolve, it would demonstrate what all urban landscapes,

as infrastructures, have the opportunity to accomplish: to define urban

territories in which all citizens might shape the city of their imaginations

and the city they wish it to become.For a full-color, multimedia presentation

of the image accompanying this essay, contact the author at kpoole@virginia.edu

for access to the larger Back Bay Fens project website, currently under

construction

.NOTES

1 For a more complete historical account and discussion of the Back Bay

Fens’ infrastructural roles, look for the author’s article forthcoming

in Landscape Journal.

2 The essay builds upon the important work of my predecessors, in particular,

Cynthia Zaitzevsky, Anne Whiston Spirn, and Catherine Howett. What distinguishes

the essay is its departure from their consideration of the Fens as an

infrastructure at singular moments in time, either when Olmsted originally

designed it and/or in the present day.

3By definition, a fen is a peat-accumulating

wetland that receives some drainage from surrounding mineral soil and

usually supports marshlike vegetation.

4 Howe, 1.

5 Barbara W. Moore and Gail Weesner,

Back Bay: a Living Portrait (Boston: Century Hill Press, 1995), p. 8.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Many thanks to Camille Wells, who in

her usual collegial manner, helped a hunch take historical form.

9 Arthur Muir Whitehill, Topographical

History of Boston, p. 100.

10 Oscar Handlin, Boston’s Immigrants

1790-1880: a Study in Acculturation (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard

University Press, 1959), p. 157.

11 Whitehill, op. cit., p. 101.

12 Whitehill, op. cit., p. 32.

13 Moore and Weesner, op cit., p. 11.

14 Moses King, The Back Bay District

and the Vendome (Boston: Moses King, 1880), p. 5.

15 John Charles Olmsted's comment is

found in his "Perambulatory Tour" with Arthur Shurtleff in A.

A. Shurtleff. October 7, 1910. Notes On Perambulatory Trip Through the

Park System With Mr.Olmsted and Mr. Pettigrew.

16 John Freeman refers to them as "squalid

shacks" in John Freeman, Report of the Committee on Charles River

Dam (Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Co., 1903), p. 195. Weesner

refers to them as "shanties," op. cit.

17 John Brinckerhoff Jackson, American

Space: the Centennial Years 1865-1876 (New York: W. W. Norton & Company,

Inc., 1972), p. 128.

18 Main Drainage, pp. 19-20.

19 Moore and Weesner, op. cit., p.8.

20 In part the Fens was riding on the

coattails of Back Bay, as the district had always been planned as a district

for prestigious institutions. Yet, these corporate entities made clear

choices to locate directly adjacent to the Fens and to orient their structures

to take best advantage of it.

21 30th Annual Report of The Board of

Commissioners for the Year Ending January 31, 1905. Boston Parks Commission.,

p. 7.

22 Shurtleff, op. cit., pp. 14-15.

23 The Fenway. Boston 200 Neighborhood

History Series (The Boston 200 Corporation, 1976).

24 Record American. Friday, July 10,

1970. Text by David Rosen, Photos by Earl Ostroff and Richard Chase.

25 The balance is precarious because

that same cloaking makes the Fens a landscape of fear. Numerous muggings

and hate crimes have been leveled against queer couples and individuals

in the Fens. The landscape that allowed a community to develop also makes

it a dangerous one.

26 Frederick Law Olmsted. Parks and the

Enlargement of Towns.

27 Pressley Associates/Walmsley Associates,

The Emerald Necklace Plan for Restoration. (Boston, 1983).

28Walmsely/Pressley Joint Venture. 1989.

Emerald Necklace Parks Master Plan. Prepared for the Department of Environmental

Management, Homestead Historic Preservation Program.

|